%20(1).jpg)

Winsor Kinkade (she/they) is an artist and community mental health social worker living and working on unceded Chiguan Chagunte territory in Half Moon Bay, California. Kinkade grew up on the coast of Northern California inspired by her natural surroundings and mentored by her father, artist Thomas Kinkade. She earned her Bachelor’s degree in Communications Studies and Fine Art at the University of San Francisco in 2017. Winsor earned her Master’s degree in Social Work at San José State University in 2019. Winsor emphasized in Children, Youth, and Families, and earned additional credentials in Pupil Personnel Services and Spanish Counseling. After studying both art and social work, they began working with art as a therapeutic process that aids in healing trauma.

Winsor’s art aims to portray the world in a non-curated way while honoring the intrinsic beauty within it. They work with varying mediums, including oil and acrylic paint, ink, and graphite, and strives to tells stories, exercise honest communication, and create both an internal and external effect. Winsor believes art is a powerful form of protest, one that offers solidarity and growth. Their ultimate goal is to weave tight-knit and communal resistance and practice collective care through her artistic practice. Winsor recalls when she was young being scolded for staring at people, particularly their hands. What an incredible amount of questions arose through this innocent investigation. To avoid gazing too long, she thought of questions she could ask others to describe people’s hands: Tell me, are they wrinkled, dirty? How are their fingernails? What color is their nail polish? Tell me, are they holding another? How long have they enjoyed this tender embrace? Are they newly getting acquainted or are they a familiar reach? Please, tell me such a rich story about whom they are attached. Can anyone know enough about another life?

Her latest body of works shares an intimate look at family members’, friends’, and strangers’ hands. They reveal some answers to the desperate questions about their stories – only this time, without shame or fear of being scolded for looking, staring, wondering.

When did you first begin creating art?

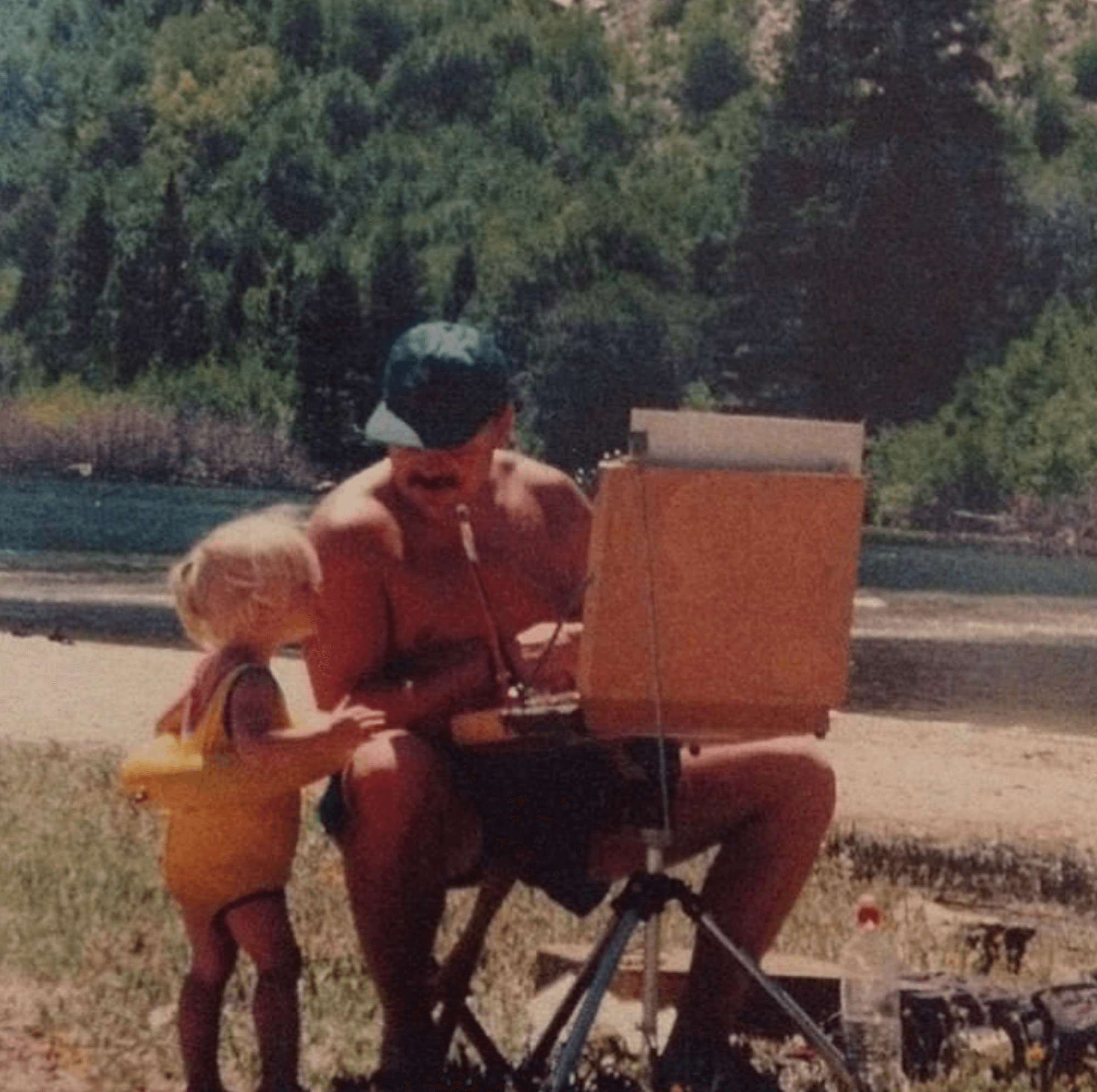

One of my favorite photos from my childhood is of me, about three years old, looking up at my dad as he paints plein air by a river. From a young age, my dad would take us to climb hills, walk along the bluffs by the ocean, or visit a nearby pond to sketch, paint, and be in connection with the land. I feel immensely grateful to have been surrounded by the healing power of creative expression since the start. Each chapter of my life from the very start has been intertwined with creating art, and I have every intention of keeping it that way.

When did you first consider yourself to be an artist?

For as long as I can remember I’ve identified as an artist. In 4th grade, I entered a school-wide art contest. I still remember what I submitted: a watercolor featuring a colorful collection of different insects surrounded by oak leaves. When it was announced that I had won the contest, I felt truly recognized, deeply seen. From that day on, not only did I consider myself an artist, but others around me did as well.

Who or what influences your practice?

My day job is as a community mental health social worker. I typically use art as a form of therapeutic expression with my clients. I went into this field initially because of my own experience with mental health struggles throughout my life and in the lives of those closest to me. As a queer artist, I recognize the importance of using art as a method of healing and understanding ourselves and others. Indeed, art has, on more than one occasion, saved my life. Some of the most healing and influential moments I have experienced have been through creating or witnessing art that moves me. Painters like Jeffrey Cheung, Bisa Butler, poets like Mary Oliver. These influences have helped to inform my artistic practice to be one that aims to evoke emotion and perhaps inspire action in the viewer.

Tell us about a specific moment in your career that you would consider a turning point.

I’m not sure I’ve had that moment yet! But there certainly have been many important, precious moments along the way. The start of the pandemic was one such defining moment for my paintings, specifically for my ongoing series that highlight people’s hands. The series was born out of a desire for connection with others in a time where there was such fear of intimacy of any kind — including that of a handshake or friendly embrace. I craved closeness and that feeling of being swept away that only comes when someone shares their life story. In the early stages of thinking about this body of work, I came to a final question: Can anyone know enough about another life? This became the title of the first painting of the series. There are currently 10 paintings in the series, and counting.

Where would you like to see your artwork go in the future?

I believe in the transformative power of personal expression alongside collective action. I believe creating art can be one way of exercising radical hope. The very act of creating art is an act of hope, of protest – in that moment, we believe we are capable of making something new. Art and social change are often woven together in a seamless way. I would like to see my art act as a form of activism through various mediums, all with the common goal of bringing attention to and divergence from our current systems of oppression. Artistic activism, as a cultural approach, is crucial for political and social resistance. My hope is to create moving experiences that prompt people to question the world as it is, imagine a world as it could be, and join together in community to make that new world real.

Radical solutions to systemic oppressions require creativity and imagination similar to that used in art making. With QTDBIPOC artists and individuals like André Henry, Morgan Harper Nichols, Alok Vaid-Menon, and Favianna Rodriguez leading the way, it is possible to imagine something, someday, beyond what we have now.

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20(1)%20(1).jpg)

.jpg)