Let’s begin with your artistic background. Have you always considered yourself an artist?

If you ask my mom, she claimed I was always an artist! I was writing poetry as early as second grade, and she saved all of my poems until I began hiding them in my journals, but I didn’t consider myself an artist until I began making sculpture in high school. My school had a really great sculpture program and it was always my favourite subject. My mom encouraged me to get a summer job at Sloss Furnaces, an old pig iron factory that was saved by artists in Birmingham, Alabama, and I worked the there as early as 15 years old as a part of their youth apprenticeship program making products for the museum to sell. I learned lost wax casting, fabricating and blacksmithing, mostly in steel and iron. I liked the physical labour; making sculpture is very laborious, and it taught me to not be afraid or intimidated of hard work at an early age.

Your artwork is mainly focused in sculpture, installation and performance. How did you come to concentrate on these modes of art making? Have you ever experimented with more traditional art forms?

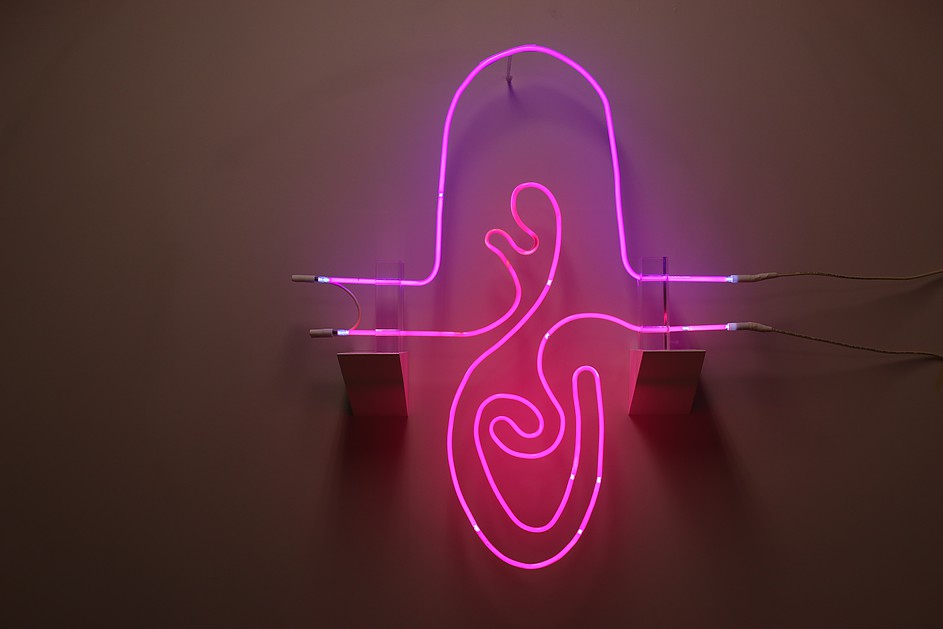

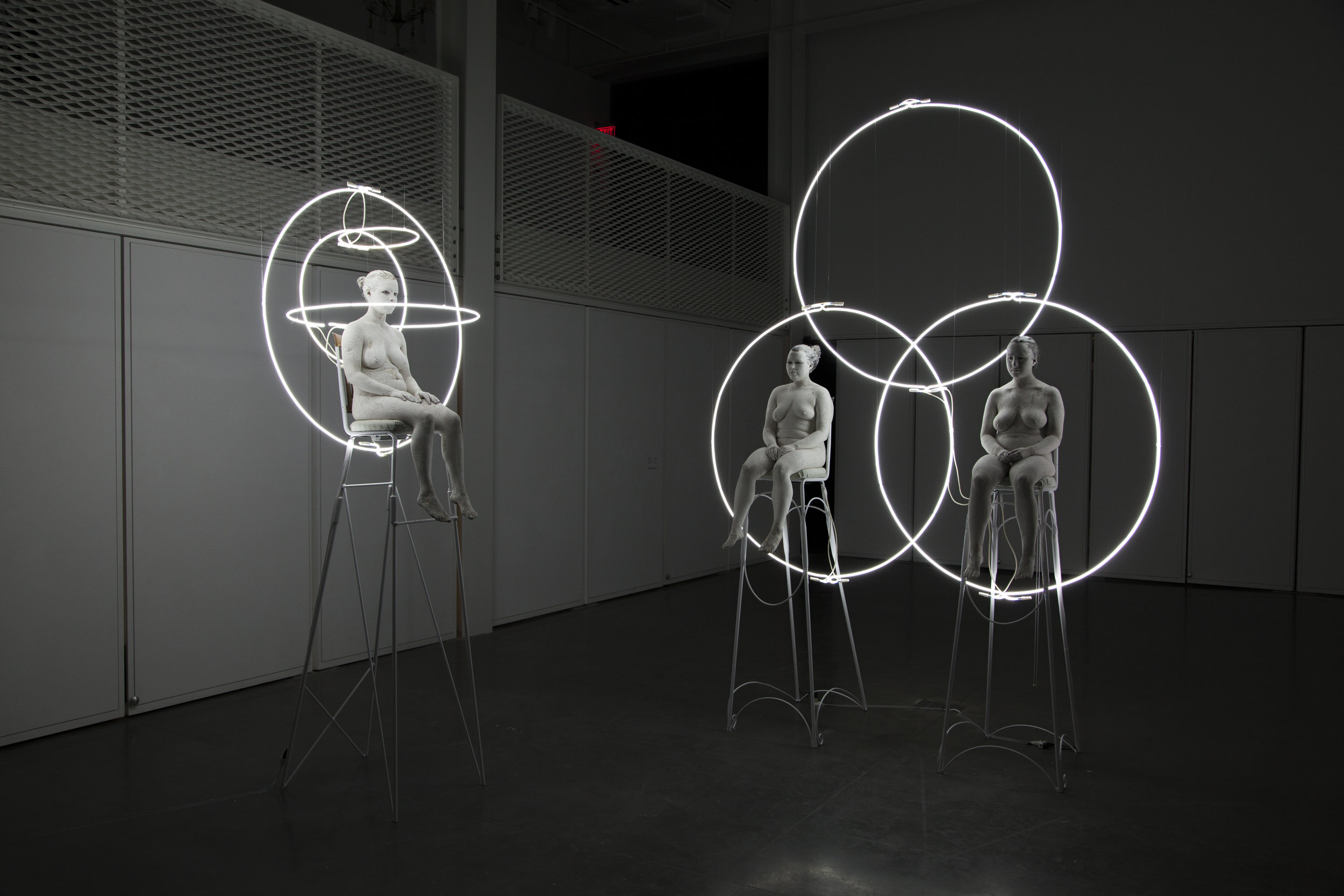

I started working with light and performance in college. I had a head start having learned metal casting in high school, and I was primarily making traditional objects when I first began to seriously make fine art. The act of metal casting is performative in nature and it was what always enticed me to use the medium. The molten metal was so powerful and full of life, and I began to see the finished product as a cold sculpture that did not carry the same energy and vitality. I was in school at Alfred University and was learning a lot about glass as a material, which was also a very heat intensive and alchemic process. The University has a neon shop, and as soon as I lit up my first tube it was love at first sight. It was like making sculpture with liquid light. It seemed to be the only material that had me coming back, so I stuck with it. I began incorporating it with choreographed performances, using live bodies as art subjects. It struck me how beautiful the human form is when illuminated, and how uncomfortable people are around nude bodies in 2017. For a long time I was investigating the naked body and using it as a symbol of the human spirit. It added an element of ‘aliveness’ that I found in molten metal and glass; a living, breathing, moving medium. I found performance work entirely more effective for my practice than still sculpture.

Many of your works embody themes of mysticism, phenomena and performative spirituality that often engage the viewer in an interactive way, such as your installation Requiem for Clarity. Can you tell us a bit about this quality of your work?

Yes! I grew up in Birmingham, Alabama, surrounded by folk art and evangelists. I read a lot, and growing up in the south you end up reading a lot of Southern Gothicism, which has themes of the uncanny and the supernatural. People are very superstitious in the South, and the tenacity of religion is so potent that you end up witnessing a lot of strange systems of belief. This culture is what shaped my approach to the subject of my practice. I am a highly sensitive and emotional person, but never liked the blind religiousness of the Bible belt, so I began to read about other modes of spiritualism, eventually landing on Theosophy, which is an esoteric comparative study on religion and the occult based in philosophy. I consider my work as a kind of personal theosophy. Art for me has always provided the same fulfilment and meaning that people get out of religion. Community, transcendence, edification; I suppose I approach transcendence, or whatever you want to call it, through art. It’s a way of meditation and it connects me to a higher purpose. I want to invite people for a moment to consider that there may be multiple channels to approach the spiritual and metaphysical sides of our bodies and minds instead of the purely traditional methods, which have been relatively unchanged for thousands of years.

I often use spectacle, light, and performative ritual to induce this feeling. I think of my work in terms of the absolute; I try and encompass the omnipresence and interconnectedness of all living and inorganic life, and often use circles as a symbol of this. In my piece Requiem for Clarity, I wanted to push on the sacredness and importance of water outside of the frame of reference of structured religion. Water is such a fascinating material and so undervalued. I wanted to bring the viewers attention to the centrality and power that water holds in our lives for all organic matter as well as for psychic and spiritual cleansing. I went around for weeks with a jug of water, getting every spiritually trained person I could find to bless the water, from internet ordained ministers to psychics, priests, reiki workers and medicine people. The water became the centerpiece of the installation. I attached it to hidden electronic sensors, so that when someone went to touch the water, it immediately triggered a change of lighting in the environment. My intention was to draw people in with the light system, enhancing the magic of water with my own bit of magic. All you need to see magic is a change of belief; and I hope that my work edges people toward seeing the everyday with a sense of awe, and seeing our lives as a miraculous and mysterious thing.

What are some of the challenges working with glass and neon as a material?

The biggest challenge in making my work is how fragile it is. Shipping and showing my work can be agonizing, and it takes a substantial amount of time and recourses to coordinate, especially if I can’t be there to install it or pick out and train performers.

You are currently an artist-in-residence at Elsewhere Museum in North Carolina. How has this experience influenced your practice? Tell us about some of the work you are doing in this unique space, which occupies the space of a former thrift store.

Elsewhere Museum is in a former thrift store from the 1950’s, so it’s like a time capsule. Artists are invited to work with the collection like a limited resource, never destroying material past the point of it’s re-use, and are also encouraged to collaborate, either with other residents or with past artists through their work. People end up working on top of each other, so every work of art is actually made by multiple different artists.

Being a resident at Elswhere has solidified the foundation of my work more than anything. While I was there I spent a month researching and re-enacting old southern superstitions, majorly collected from the Appalachian Mountain region. I learned a lot working on this project, studying the irreligiousness of superstitions, and the peculiar nature of people when left to their own devises. It was spooky, performing all of these rituals and not knowing what to expect of them. I sewed locks of hair into my pants (to make others fall crazy for you) I re-enacted a dumb supper, where you silently cook a meal of unleavened bread and water, moving backwards through all of the motions, including walking backwards and setting the table backwards, and waited until midnight to meet the ghost of the man I would marry. He never showed up! I looked up Bible verses that set blood in the body (Ezekiel 16:6) memorized the verse and recited it over anyone with a cut- I mean some of these things were just absolutely whacky.

I chose to work in the Haint room of the museum, which is the most haunted room in the old building and the room with the most spectral sightings. It’s an old superstition to paint ceilings of window-facing rooms or porches blue, to help drive bad spirits out of the house, and you can see the residual blue paint on the ceiling. I chose to fill the Haint room with lamps from the collection, suspending them in mid air and putting blue light bulbs in them, and embroidered some of the text of the superstitions into pillows and lamps. I wanted to create a more social space in the room, which was generally not used, where people could experience these superstitions and decide for themselves their relevancy or usefulness in the modern day South.

What role does collaboration have in your practice? How does it specifically affect your performances where you have people performing other than yourself?

Collaboration is vital to my work, not to mention it makes a studio practice fun and you are capable of achieving much more! I often collaborate with other artists from start to finish on a piece, like my newest work with Krista Davis, Neverending In All Directions // On This Page The Map Is Unwritten. It takes less pressure off of the idea making and execution of the work. It’s always useful to have someone to bounce ideas off of, especially if you work along similar veins of subject matter.

I enjoy choreographing my work instead of performing in it because often times the performers I pick will have skills that I don’t have- it could be physical or aesthetic. It’s like a tool- I’m not the best performer, so I try and find people who can do a better job than me. I find that dancers are more self-aware and have more control of their bodies, and actors can put on any persona you could possibly think up. I do smaller performances for the camera, but usually these are personal and have an intent of working out something that’s going on in my life that I feel like I can personally accomplish, like my work with Jess Hirsch called Mourning the Missisippi. In that case, I felt like I needed to perform the work because I had the ability and the resolve to perform- for me it was a healing ritual.

What performance artists do you look to for inspiration and motivation?

The list is endless!! My primary inspiration comes from reading about and attending religious rituals, and most recently I have been really inspired by Native American ceremonies, which are prevalent in the Southwest. As far as performing artists, I love Ana Mendieta, La Pocha Nostra, Ernesto Pujol, Postcommodity, and Simone Leigh, and of course the king of performance, Joseph Beuys.

Can you tell us about any upcoming projects you have coming up?

I am curating a show this September called GOOD WONDER, which is really exciting, and my Graduate Thesis show is coming up in January, so I’ve mostly been working towards that exhibition, researching themes of Iconoclism and Iconoclash. I’m beginning to work with plants and animals in my work as well, which is an incredibly new and scary direction to head in, but I’m very excited and looking forward to finishing graduate school.